.png)

The Growing Up in New Zealand

Extreme Weather Survey

Weather Survey Report 1

Who are the cohort?

Overall, 680 young people and 817 mothers/primary caregivers participated in the Extreme Weather Survey. From these participants, there were 667 family units, meaning that both the young person and mother/primary caregiver took part in the study.

Weather Survey Report 2

Preparing for extreme weather events

Information and resources for preparing for extreme weather events are crucial for response and recovery. This could refer to information about getting your household, work, or school ready before an emergency.

Weather Survey Report 3

Housing: Evacuation, condition, and damage

In the aftermath of the extreme weather events, many people were forced to evacuate their homes (temporarily or permanently) and/or to repair damage that was caused by the severe weather.

Weather Survey Report 4

Access to services

Extreme weather events can destroy infrastructure needed for services such as power, water, and telecommunications. Across the North Island, Cyclone Gabrielle caused wide spread damage to power line networks, with 332,000 households cut off during the cyclone.

Weather Survey Report 5

Mental health

The destruction and stress caused by an extreme weather event can take a toll on the mental health of individuals, families and communities. Young people and their families may experience elevated mental ill-being symptoms during, following, and even months after the floods or cyclone.

Weather Survey Report 6

Physical health

Physical health and safety can be directly or indirectly affected by extreme weather events.Hazards caused by the Auckland Anniversary Weekend Flooding and/or Cyclone Gabrielle put people at risk of injury and, in some cases, mortality.

What are extreme weather events?

Extreme weather events are occurrences of severe weather, such as heat waves, droughts, cyclones, and floods [1]. Extreme weather events can have disastrous impacts on communities and infrastructure [1]. The concentration of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere is increasing, causing changes in climate [2, 3]. In Aotearoa, New Zealand, climate change might look like higher temperatures, rising sea levels, and less snow and ice [2, 3]. Climate change also means that extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and intense [2, 3].

What were the recent extreme weather events in Aotearoa, New Zealand?

Aotearoa, New Zealand, had two extreme weather events at the beginning of 2023: the Auckland Anniversary Weekend Flooding and Cyclone Gabrielle. The long-term (six-month) impact of these extreme weather events on rangatahi/young people and their whānau/families is investigated in this report.

Auckland Anniversary Weekend Flooding

Beginning on the 27th of January 2023, Auckland suffered a 1-in-200 year flooding event, with 245mm of rainfall in under 24 hours [4, 5]. Widespread flooding occurred, particularly in South, West, and Central Auckland and the North Shore [6]. Over 26,000 houses lost power due to the extreme weather [5]. By the 3rd of February, 39 roads were closed and 209 houses were red-stickered (residents can no longer enter the property) [5]. If you, or someone you know, need additional information on the Auckland recovery from extreme weather and natural disasters, please see https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/recovery-extreme-weather-disasters/Pages/default.aspx.

Cyclone Gabrielle

Between the 12th and 16th of February 2023, Cyclone Gabrielle arrived in Aotearoa, New Zealand [7]. Cyclone Gabrielle brought severe rainfall, winds, and flooding [7]. The government declared a National State of Emergency on the 14th of February, which was only the third time in New Zealand history [8, 9].

Cyclone Gabrielle affected many North Island regions, including Northland, Auckland, Bay of Plenty, Waikato, Hawke’s Bay, and Gisborne [7]. Cyclone Gabrielle caused widespread damage to land and housing as well as put people’s lives at risk [7, 8]. In particular, Hawke’s Bay and Gisborne experienced devastating consequences from the intensive rainfall and flooding [10, 11]. If you, or someone you know, need additional regional information on extreme weather events, please see https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/find-your-civil-defence-group.

Extreme weather events can have negative impacts on important services and property. Infrastructure needed for essential services such as power and water can be badly damaged [12, 13]. Disruption of these services can impact health care and community networks [13]. Extreme weather events can also cause destruction to properties, meaning that people are forced to evacuate their homes or organise repairs [12]. Multiple relocations following an extreme weather event are common [12]. Furthermore, in Aotearoa, New Zealand, low-income households are disproportionately affected by severe weather [14]. Disadvantaged households more often live in low-cost housing and rent in high-risk areas [14]. These households may not have access to the resources they need to repair or relocate [14].

Extreme weather events can also have negative consequences for mental and physical health. Extreme weather or natural disasters are related to increases in post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, and anxiety in adults and young people [12, 15-18]. These effects can persist for months or even years [15, 19]. Furthermore, those exposed to severe weather conditions are at risk of injury, disease, and worsening of chronic illnesses [12, 18, 20].

Rangatahi/young people may be particularly vulnerable during an extreme weather event. Important developmental processes occur during adolescence, including biological, hormonal, and brain changes [21, 22]. These changes can mean that young people feel less able to cope with stress and uncertainty [12, 15, 23]. During an emergency, young people may feel they have little control over what is happening around them [15]. Therefore, family and community support are very important during extreme weather events, especially for rangatahi [15, 23].

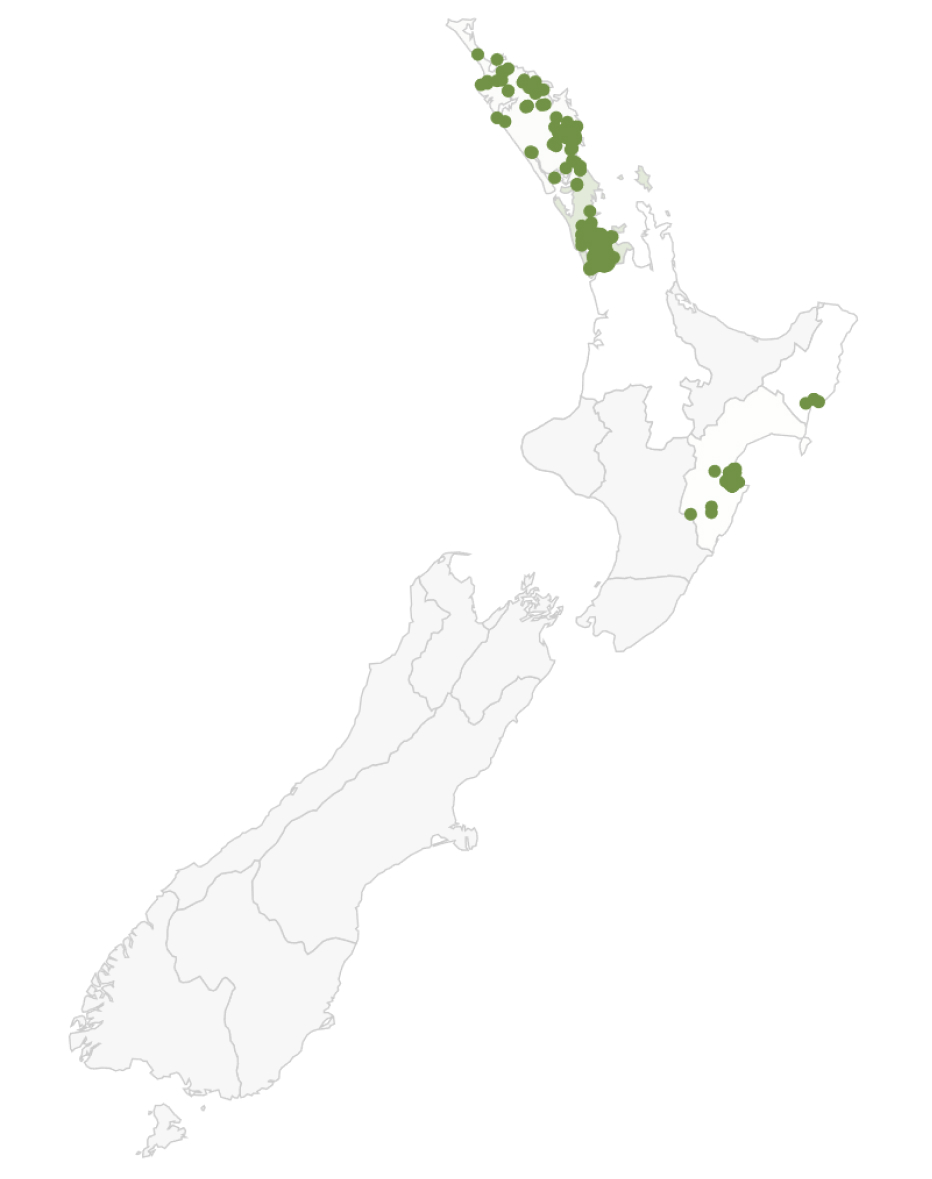

To understand the impact of extreme weather events on the health and wellbeing of rangatahi/young people, New Zealand’s largest longitudinal study, Growing Up in New Zealand, reached out to 1463 young people and 1443 mothers/primary caregivers in August 2023. During this data collection period, young people in the Growing Up in New Zealand cohort were aged 13-14 years, with many living in the areas most severely affected by the floods and/or cyclone, including Auckland, Northland, Hawke’s Bay, and Gisborne.

Growing Up in New Zealand asked 680 rangatahi/young people and 817 mothers/primary caregivers about their experiences during and after the floods and/or cyclone. These extreme weather events occurred at the start of the 2023 school year, which may have disrupted educational experiences. Damage to infrastructure and housing may have impacted social connectedness and access to health and social services.

If you think you, or someone you know, may be experiencing hardship or poor health, there are several free tools, information guides, or services that can help.

Resources for extreme weather events

See the Civil Defence National Emergency Management Agency website (https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/find-your-civil-defence-group) for more information on extreme weather events, and information on preparing for an emergency.

See the regional civil defence groups for local information: https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/find-your-civil-defence-group

See the Ministry for the Environment website for information on recovering from recent severe weather events: https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/areas-of-work/recovering-from-recent-severe-weather-events/

See the Fire and Emergency website for safety tips and support for extreme weather events: https://www.fireandemergency.nz/incidents-and-news/extreme-weather-events/

See the Whaikaha Ministry of Disabled People website for information on where to go for help for extreme weather: https://www.whaikaha.govt.nz/news-and-events/news/extreme-weather-where-to-go-for-help/

Resources for mental and physical health

See the Ministry of Health website (https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/services-and-support) for a list of resources or click below for information or support:

Need to talk? Free text or call 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor, or see https://1737.org.nz/

For wellbeing support near you including for Youth, Kaupapa Māori, Pacific-led see https://www.wellbeingsupport.health.nz/

Support for rangatahi to find support for hauora, identity, culture, and mental health,see https://www.thelowdown.co.nz/

Healthcare providers near you, see https://www.healthpoint.co.nz/mental-health-addictions/?programmeArea=im%3A42a1e54a-a52d-4c63-b91a-18714aef1c38

Youthline – Free, confidential and non-judgemental, phone 0800 376 633, free text 234, email talk@youthline.co.nz or use the online chat: www.youthline.co.nz/web-chat-counselling.html

You can find Māori Health Providers in your area here https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/services-and-support/health-care-services/maori-health-provider-directory

Find a hauora Māori partner in your rohe here: https://www.teakawhaiora.nz/en-NZ/find-health-services

Vaka Tautua 0800 652 535 (0800 OLA LELEI) - free national Pacific helpline, email enquiries@vakatautua.co.nz . The team speaks Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islands Māori and English

Asian Family Services 0800 862 342, email or help@asianfamilyservices.nz - provides professional, confidential support in multiple languages

Rainbow mental health organisation OutLine provides free support: free phone 0800 688 5463 or free online chat via https://outline.org.nz/

Methods

Who participated in this study?

Families from the Growing Up in New Zealand cohort living in regions affected by the 2023 extreme weather events were invited to participate. These regions included Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland (n = 1838, 91.5%), Te Tai Tokerau/Northland (n = 105, 5.2%), Te Matau-a-Māui/Hawke’s Bay (n = 59, 2.9%), and Te Tai Rāwhiti/Gisborne (n < 10).

How did we collect data?

The Extreme Weather Survey data was collected from August 1 to September 3, 2023. The Extreme Weather Survey consisted of two online questionnaires; one answered by young people, and one answered by the young person’s mother/primary caregiver. Email invitations were issued to all eligible participants.

Each eligible young person and mother/primary caregiver received an individualised link within their email invitation. This link directed them to the web-based online survey, accessible on all devices (computer, tablet, and phone). This was complemented by telephone follow up from an experienced interviewer and/or centralised community support for families requesting assistance.

Telephone and text messaging helplines were available between 9 AM – 9 PM 7 days a week for the duration of the data collection.The young person’s questionnaire consisted of 90 questions and took approximately 15 minutes to complete, and the mother/primary caregiver questionnaire consisted of 237 questions and took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Electronic consent and assent forms was completed online by the mother prior to completing the questionnaire.

How did we report the data?

Here we report descriptively who took part in the Extreme Weather Survey, how prepared people felt for the extreme weather events, as well as about housing conditions, evacuation, access to services, and mental and physical wellbeing. These key themes are reported in relation to how affected people felt by the extreme weather events. Young people and mothers/primary caregivers were asked about changes that may have occurred in their life due to floods and/or cyclone.

Young people reported if they were affected by the floods and/or cyclone; “Yes” (Affected), “No, but someone I know was” (Know someone else affected), or “no” (Not affected). Mothers/primary caregivers also reported if they were affected by the weather events; “Yes” (Affected), “No, the area I live in was affected” (Live in an area affected), or “no” (Not affected). Consequently, some people reported that they were not affected by the extreme weather events despite experiencing some impacts.

This is because the extreme weather events may not have changed their everyday life. In this sense, we are able to get a subjective understanding of how people were affected by the extreme weather events. We then report if people were affected by other important factors that typically follow extreme weather events, such as damage to housing, impact on school, transport, services, other activities and mental and physical wellbeing.

Figure 1. Shows the high-level regional location of young people during the floods and/or cyclone who took part in the Growing Up in New Zealand Extreme Weather Survey.

References

Suggested citation: Gawn, J., Fletcher, B.D., Neumann, D., Pillai, A., Miller, S., Park, A., Napier, C., Paine, S.J. (2024). The impact of extreme weather events on young people and their families: Evidence from Growing Up in New Zealand. Auckland: Growing Up in New Zealand. Available from: www.growingup.co.nz

National Emergency Management Agency. Storms and severe weather. Retrieved from https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/cdem-sector/consistent-messages/storms-and-severe-weather

Ministry for the Environment, National Climate Change Risk Assessment for New Zealand: Snapshot. 2020.

Jay, A., et al., Overview, in Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II, D.R. Reidmiller, et al., Editors. 2018: U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. p. 33-71.

NIWA. Auckland suffers wettest month in history. 2023; Available from: https://niwa.co.nz/news/auckland-suffers-wettest-month-in-history.

New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, The 2023 Auckland Anniversary weekend storm: An initial assessment and implications for the infrastructure system 2023.

Newsroom. Auckland’s historic flooding explained in five charts. 2023; Available from: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/sustainable-future/aucklands-historic-flooding-explained-in-five-charts#:~:text=The%20longest%20running%20weather%20record,that%20lasted%20nearly%20four%20decades.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Cyclone Gabrielle’s impact on the New Zealand economy and exports: A market intelligence report. 2023.

Wilson, N., A. Broadbent, and J. Kerr, Cyclone Gabrielle by the numbers – A review at six months. 2023: Public Health Communciation Centre and Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington.

National Emergency Management Agency. Declared States of Emergency. 2023; Available from: https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/resources/previous-emergencies/declared-states-of-emergency.

Hawkes Bay Regional Council. Cyclone Gabrielle impacts. 2023; Available from: https://www.hbrc.govt.nz/our-council/cyclone-gabrielle-response/cyclone-gabrielle-impacts/.

NZTA. Hawke's Bay cyclone recovery. 2023; Available from: https://www.nzta.govt.nz/projects/hawkes-bay-cyclone-recovery/.

Simpson, D.M., I. Weissbecker, and S.E. Sephton, Extreme weather-related events: Implications for mental health and well-being, in Climate change and human well-being: Global challenges and opportunities. 2011, Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, US. p. 57-78.

Curtis, S., et al., Impact of extreme weather events and climate change for health and social care systems. Environmental Health, 2017. 16(S1).

Te Uru Kahika, Before the deluge: Building flood resilience in Aotearoa. 2022.

Barkin, J.L., et al., Effects of extreme weather events on child mood and behavior. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 2021. 63(7): p. 785-790.

Beaglehole, B., et al., A systematic review of the psychological impacts of the Canterbury earthquakes on mental health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 2019. 43(3): p. 274-280.

Fergusson, D.M., et al., Impact of a Major Disaster on the Mental Health of a Well-Studied Cohort. JAMA Psychiatry, 2014. 71(9): p. 1025.

Rocque, R.J., et al., Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open, 2021. 11(6): p. e046333.

Beaglehole, B., et al., The long-term impacts of the Canterbury earthquakes on the mental health of the Christchurch Health and Development Study cohort. Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry, 2023. 57(7): p. 966-974.

Ebi, K.L., et al., Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annual Review of Public Health, 2021. 42(1): p. 293-315.

Dahl, R.E., et al., Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 2018. 554(7693): p. 441-450.

Eiland, L. and R.D. Romeo, Stress and the developing adolescent brain. Neuroscience, 2013. 249: p. 162-171.

Ma, T., J. Moore, and A. Cleary, Climate change impacts on the mental health and wellbeing of young people: A scoping review of risk and protective factors. Soc Sci Med, 2022. 301: p. 114888.

Perry, B., The material wellbeing of New Zealand households: trends and relativities using non-income measures, with international comparisons. 2015: Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Social Development.

Perry, B., The material wellbeing of NZ households: Overview and Key Findings from the 2017 Household Incomes Report and the companion report using non-income measures (the 2017 NIMs Report). . 2017: Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Social Development. .

Turrell, G., A. Kavanagh, and S.V. Subramanian, Area variation in mortality in Tasmania (Australia): the contributions of socioeconomic disadvantage, social capital and geographic remoteness. Health Place, 2006. 12(3): p. 291-305.

Ministry of Education. Severe weather event education update. 2023; Available from: https://www.education.govt.nz/news/severe-weather-event-education-update/

Ministry of Education. Severe weather event and school closure. 2023; Available from: https://www.education.govt.nz/news/severe-weather-event-information/

Ministry of Education, Schools On-site Attendance 13 February 2023 –17 February 2023. 2023.

Ministry of Education. Severe weather event: Cyclone Gabrielle update. 2023; Available from: https://www.education.govt.nz/news/severe-weather-event-tropical-cyclone-gabrielle-update/.

New Zealand Government, Summary of Initiatives in the North Island Weather Events Response and Recovery Package. 2023.

Tinetti, J. Govt to repair or rebuild all weather-hit schools. 2023; Available from: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/govt-repair-or-rebuild-all-weather-hit-schools.

Gheytanchi, A., et al., The dirty dozen: twelve failures of the hurricane katrina response and how psychology can help. Am Psychol, 2007. 62(2): p. 118-30.

IPCC, Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, in A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, C.B. Field, et al., Editors. 2012: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA,.

Insurance Council of New Zealand. 2023 Climate Disaster Payouts Top $2 Billion. 2023; Available from: https://www.icnz.org.nz/industry/media-releases/2023-climate-disaster-payouts-top-2-billion/.

Wilson, N., et al., Water infrastructure failures from Cyclone Gabrielle show low resilience to climate change. 2023: Public Health Communciation Centre and Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington.

The Spinoff. Cyclone Gabrielle: The latest official Auckland travel updates from AT and NZTA. 2023; Available from: https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/13-02-2023/cyclone-gabrielle-the-latest-official-auckland-travel-updates-from-at-and-nzta.

Auckland Transport. Updates on Repairs. 2023; Available from: https://at.govt.nz/projects-roadworks/road-works-disruptions/long-term-road-repairs-from-auckland-storms/updates-on-repairs.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., et al., Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 2010. 19(10): p. 1487-1500.

Connor, K.M. and J.R.T. Davidson, Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 2003. 18(2): p. 76-82.

Radloff, L.S., The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied psychological measurement, 1977. 1(3): p. 385-401.

Irwin, D.E., et al., An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research, 2010. 19(4): p. 595-607.

Kroenke, K., R.L. Spitzer, and J.B.W. Williams, The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2001. 16(9): p. 606-613.

Spitzer, R.L., et al., A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2006. 166(10): p. 1092.

Ministry of Health, Measuring Health States: The World Health Organization – Long Form (New Zealand Version) Health Survey: Acceptability, reliability, validity and norms for New Zealand. Public Health Intelligence Occasional Bulletin No. 42. 2007: Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Meet our team

Learn more about the people who make Growing Up in New Zealand happen.

Our newsletter

Keep up-to-date with our latest news, events and research.

Current projects

Find out more about the research projects currently underway using Growing Up in New Zealand information.

%201.svg)