Relationships with parents, peers and special adults.

In the 12-year data collection wave, young people reported their experiences of their relationships with their parents, peers and non-parental special adults.

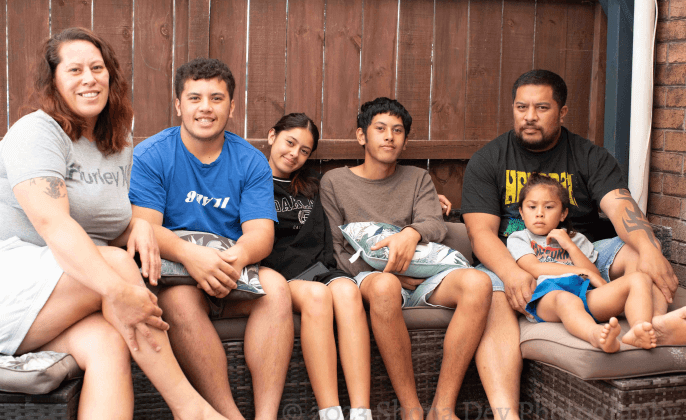

These three types of relationships are considered to be the central relationships that influence adolescent wellbeing. Examining these is important for understanding relational ties beyond the nuclear family, particularly for Māori where the concept of whānau encompasses a wider familial and non-familial system of connectedness and a collective responsibility for children.

This snapshot examines the social and familial relationships of 12-year-olds in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Who are young people’s ‘parents’?

We asked young people questions about their parents or caregivers – “the people who look after you the most”. This could be one parent if they are mainly looked after by one person in their family (e.g. Dad or Aunty), or both parents if they are normally looked after by two or more people (e.g. Mum and Grandma).

What does a close relationship mean?

It is important to note that throughout this snapshot, while we refer to relationships that are ‘less close’ or ‘less strong’, this does not mean that the relationships themselves are weak or distant. These are terms we have used to compare groups of young people who are experiencing relationships in slightly different ways. While relationships are an integral part of a young person’s life, they are ultimately dynamic, and personal, and the weight or value of each relationship is dependent on many inter-related factors, including immediate and past experiences, personal needs and goals, family dynamics as well as wider societal and cultural contexts.

To measure young people’s relationships with their parent(s) or primary caregiver(s), we used a validated 8-item scale, with questions including “I trust my parent(s)”, and “My parent(s) understands me”.

To measure young people’s experiences of their relationships with their friends or peers, we used a similar, validated, 8-item scale, with questions including “I trust my friend(s)”, and “My friends listen to what I say”.

To measure young people’s relationships with other important adults in their lives, we asked them questions about their ‘Special Adult(s)’. A special adult was by definition, “someone who does a lot of good things for you but is NOT your parent or guardian. For example someone (a) who you look up to and encourages you to do your best, (b) who really cares about what happens to you, (c) who influences what you do and the choices you make, and (d) who you can talk to about personal problems.”

For more information about the Parent-Child Relationships tool, the Peer Relationships tool and the Presence of a Special Adult tool, see Relationships – Supplementary Material.

Insight one

Young people’s relationships with their parents at age 12.

Our study found that young people generally experience positive relationships with their parents. Although young people are extending their social networks at this age and tend to spend less time with their parents, the primary caregiver-young person relationship remains central and important, as it continues to provide a framework for relating to others.

97% of young people reported that their parents accept them almost aways or often.

94% of young people told us they trust their parents almost always or often.

92% said they can almost always or often count on their parents to help them when they have a problem.

There were some differences in the parental relationship experiences of 12-year olds between ethnic groups.

Young people living in areas of high deprivation experienced less close relationships with their parents.

Insight two

Young people’s relationships with their peers at age 12.

Young people experienced positive, trusting and communicative relationships with their peers overall. We know that peer relationships are particularly important for young people aged 12 to 13 as they become less dependent on their parents and primary caregivers as the main source of social support. Peer relationships can contribute to shaping social, emotional and behavioural outcomes, and to shaping a young person’s identity and sense of self.

Young people tended to respond more positively about trust in their peer relationships compared to communication.

Cisgender girls reported stronger peer relationships than both cisgender boys and transgender and non-binary young people.

85% of young people reported that they trusted their friends almost always or often.

“Having heaps of family and friends to talk to when I am down”

Pacific young people experienced stronger peer relationships than sole European young people.

42% of young people said that their friends encourage them to talk about their difficulties almost always or often.

Insight three

Young people's relationships with other important adults.

Our study found that 48% of young people identified at least one special adult in their lives. Young people are identifying members of their extended family and whānau, including grandparents, aunts, uncles and siblings, as well as members of the community, and recognising the special and unique place they hold in their everyday lives. This is an important finding given that positive and sustained adult-youth relationships both within and outside the family are important for young people’s development and growth.

Almost half of young people had at least one special adult in their lives.

For those who had a special adult, the average number of special adults was five.

35% of young people said they didn’t have a special adult in their lives.

Rangatahi Māori and Pacific young people were more likely to have a special adult compared to sole European young people.

Young people in areas of high deprivation were more likely to have a special adult compared to those living in areas of low deprivation.

Grandparents, aunts or uncles and teachers were the most common type of special adult.

Insight four

Young people's networks of social and familial support.

We examined parent, peer and special adult relationships together to understand young people’s networks of support. We found that half of young people experienced strong relationships with parents, peers, and had a special adult in their lives, while nine out of 10 young people experienced two or three strong relationships. These are positive findings, given the connection between relational support and youth thriving.

Half of young people experienced strong relationships with parents, peers, and had a special adult in their lives.

Often where one area of support was lacking, another relationship was strong – young people can draw on multiple sources of support.

91% of young people experienced two or three strong relationships in their lives.

Just 0.6% of young people reported having less close relationships with parents and peers, as well as no special adult in their lives.

“Getting to have all the people in my life there for me and having loving and supportive family and friends”

Relevance for policy

and practice.

These results provide the opportunity to further explore whether there are any demographic characteristics of groups who experienced strong and diverse relational support compared to those who did not. Furthermore, future research could explore the positive outcomes associated with young people’s networks of support in Aotearoa New Zealand, including self-esteem, mental wellbeing and educational outcomes. See the Mental Health Snapshot for an exploration of how relationships impact wellbeing outcomes, and the Covid-19 Snapshot to read about how young people with stronger relationships with their parents were less worried about the impacts of COVID-19.

Young people are generally experiencing positive relationships.

This study found that most young people experienced positive relationships in their lives. Less than 1% of the cohort reported having poor relationships with their parent(s), peers and no special adult relationship in their lives. These are promising findings given the vision of the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy, which includes domains related to children and young people feeling ‘loved, safe and nurtured’ and ‘accepted, respected and connected’. It is crucial to support and maintain these relationships for all young people and their families, as they are associated with many positive developmental outcomes for children, including self-regulation, coping, prosocial behaviour, and long-lasting positive relationships with others.

.png)

Material support may improve parent-child relationships.

We found that 12-year-olds living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas experienced less close relationships with their parent(s) compared to young people living in other areas. This finding may reflect how experiences of poverty and material hardship disrupt the opportunity to create strong relationships between parents and children. For example, parents living in areas of high deprivation are more likely to work multiple jobs, or work night shifts, which is likely to influence how much time parents are able to spend with their child. However, we also found that young people living in areas of high deprivation were more likely to have a relationship with a special adult compared to those living in the least deprived areas, indicating the strength of collective caregiving for many families.

Collective Care – Recognising who supports our young people.

The number and diversity of special adults identified by young people illustrates that they are sourcing support from many adults in their lives, including grandparents, aunts, uncles, teachers, and siblings. 12-year-olds are identifying members of their extended family and whānau as well as members of the community, and recognising the special and unique place they hold in their everyday lives. Our findings suggest that policy interventions for children and young people should engage with young people’s broader communities, which may better reflect their diverse and complex relational networks. Further measurement and analysis of relationships including recognising who provides care and support for young people at age 12 needs to better reflect a contemporary vision of Aotearoa.

.png)

Supporting transgender and non-binary young people.

We found that transgender and non-binary young people were significantly less likely to have strong relationships with their parents compared to cisgender young people. This finding highlights the need to improve whānau support around understanding and embracing a range of gender identities. Culturally-responsive guidance is particularly important, considering that transgender and non-binary young people are part of all ethnic communities in Aotearoa New Zealand.

References and

research methods

At Growing Up in New Zealand, we're passionate about advancing research and making sure our work is informed by a wide range of sources. That's why we've included a comprehensive list of references, along with an introduction and a detailed report of the research methods used to support the Growing Up in New Zealand study.

Read the full report

We’ve carried out more than 90,000 interviews and collected more than 50 million pieces of data to help inform policy and help give children the best start in life.

Explore other snapshots

%201.svg)