Indicators of food insecurity and access to food assistance in the Growing Up in New Zealand cohort

Food insecurity is related to low disposable household income and material deprivation. It is currently used as an indicator to monitor progress in line with the Child Poverty Reduction Act (1). There is a decreasing trend since 2012/13 in the proportion of children living in households where food runs out often or sometimes (1).

Children living in households with moderate to severe food insecurity are less likely to receive the nutrition they need for healthy development (2). Compared to children in food secure households, children with food insecurity have lower fruit and vegetable intake, are less likely to eat breakfast at home before school and have more fast food and more fizzy drinks because these are cheap, filling alternatives (3). Research indicates that reducing food insecurity for children and young people through a school lunch programme improves diet quality and academic achievement (4).

This report examines the proportions of the Growing Up in New Zealand cohort that lived in households experiencing food insecurity. We focused on change in household food security status between 8- and 12-years of age, and receipt of government support for families with food insecurity, including school food programmes.

Food insecurity is defined in New Zealand as a limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited ability to acquire personally acceptable foods that meet cultural needs in a socially acceptable way (3, 7).

A person is considered “food secure” when they have the physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (as defined by the United Nations Committee on World Food Security).

Household food security was measured using an 8-item questionnaire (5) and is calculated with the same method and cut-points as used in the New Zealand Health Survey (6). For more information see the Supplementary Technical document (linked at end of page).

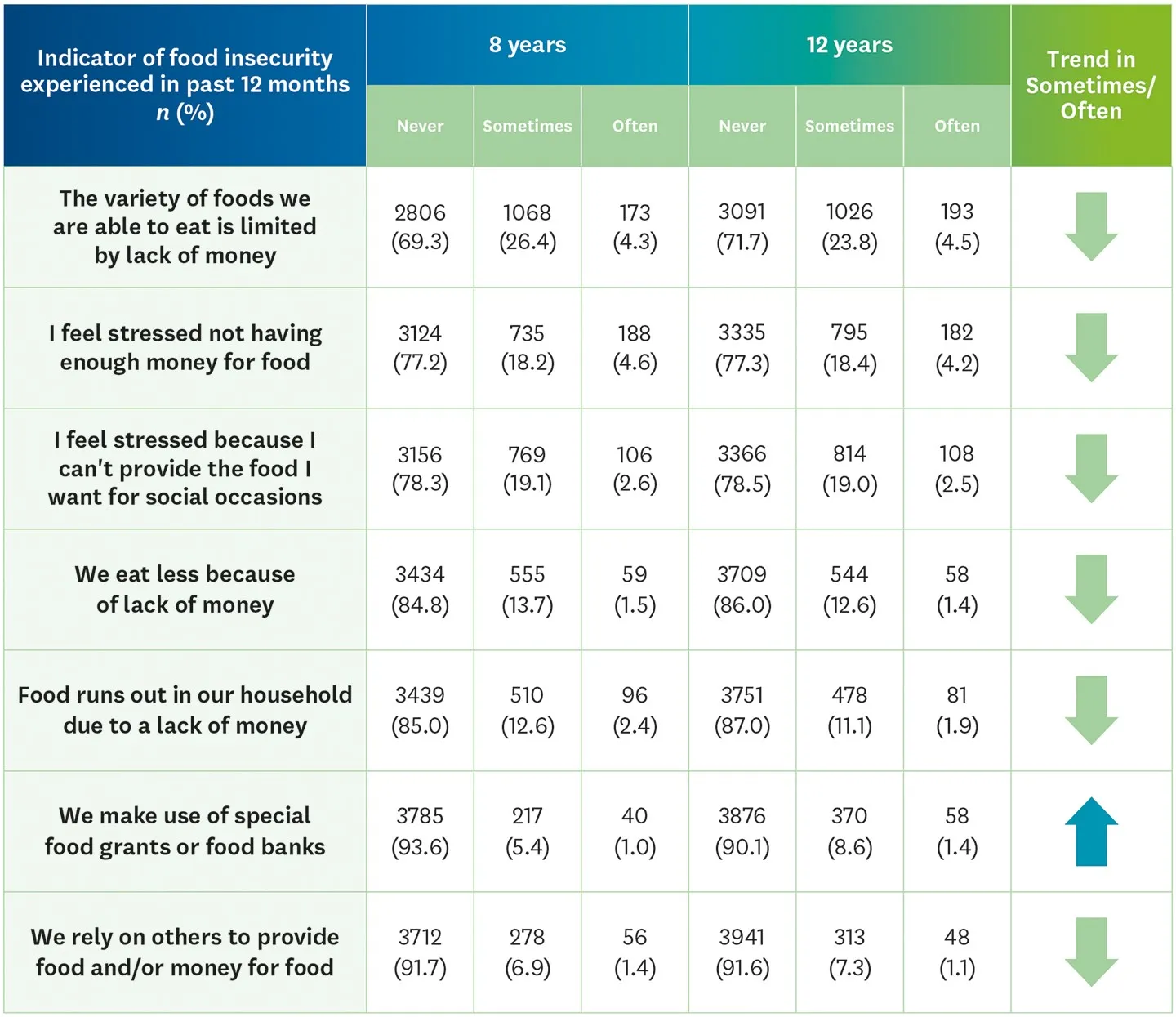

Mothers were asked how often the following statements had been true for their household in the past year (with response categories of Never, Sometimes or Often):

- We can afford to eat properly.

- Food runs out in our household due to lack of money.

- We eat less because of lack of money.

- The variety of foods we are able to eat is limited by lack of money.

- We rely on others to provide food and/or money for food, for my/our household when we don’t have enough money.

- We make use of special food grants or food banks when I/we do not have enough money for food.

- I feel stressed not having enough money for food.

- I feel stressed because I can’t provide the food I want for social occasions.

Mothers were also asked the frequency that their 12-year-olds received food at school from various charitable and government-funded food programmes, and their household’s receipt of WINZ special needs food grants, main benefits and tax credits. Child ethnicity and neighbourhood deprivation (NZDep2018) have been described in the methods section of Now We Are 12.

Insight one

Food insecurity is inequitably associated with high neighbourhood deprivation and Pacific and Māori ethnicity, but young people from all backgrounds are affected.

Four out of every five (83.1%) 12-year-olds lived in households that were food secure; 14.9% lived in moderately food insecure households and the remaining 2.0% lived in households that were severely food insecure.

(NZDep2018 quintiles: 1=Low deprivation, 5=High deprivation)

Insight two

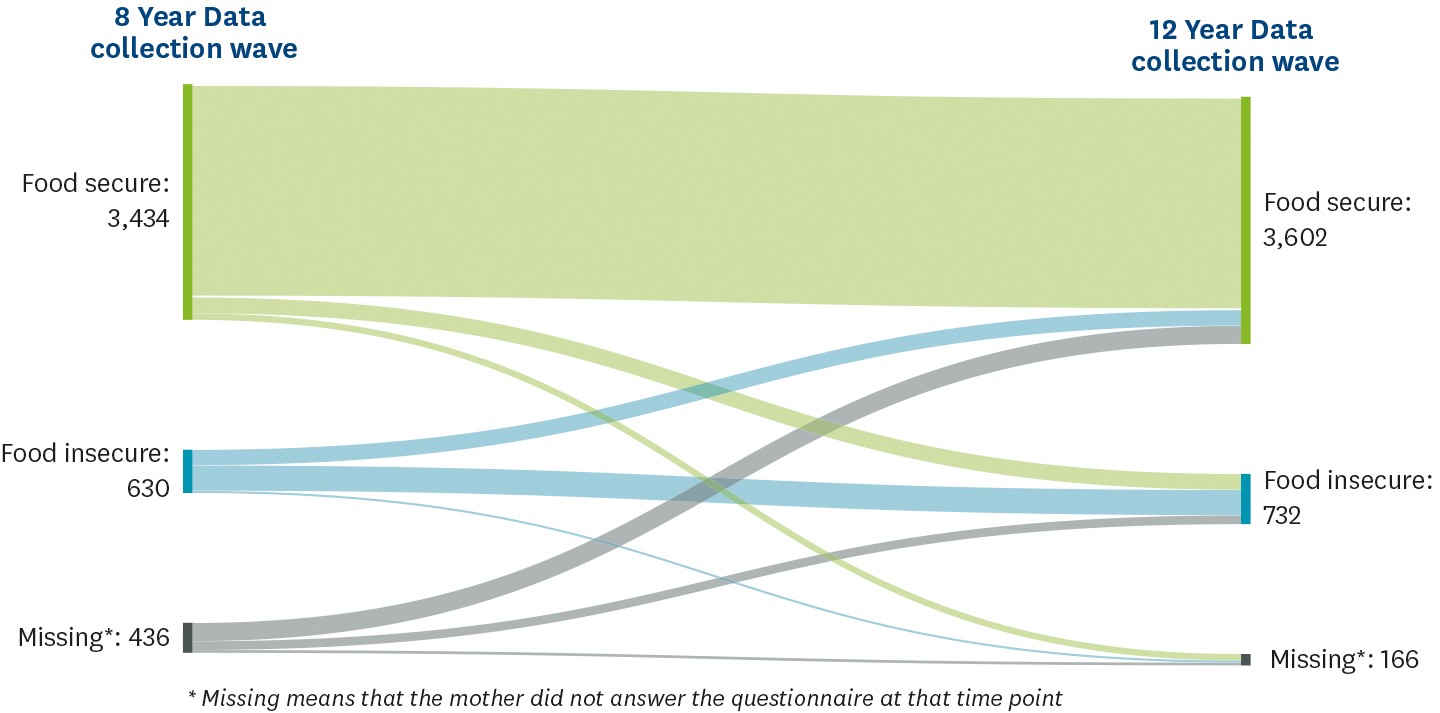

Food security within households fluctuates over time; in the past four years some families moved from being food secure to insecure and vice versa.

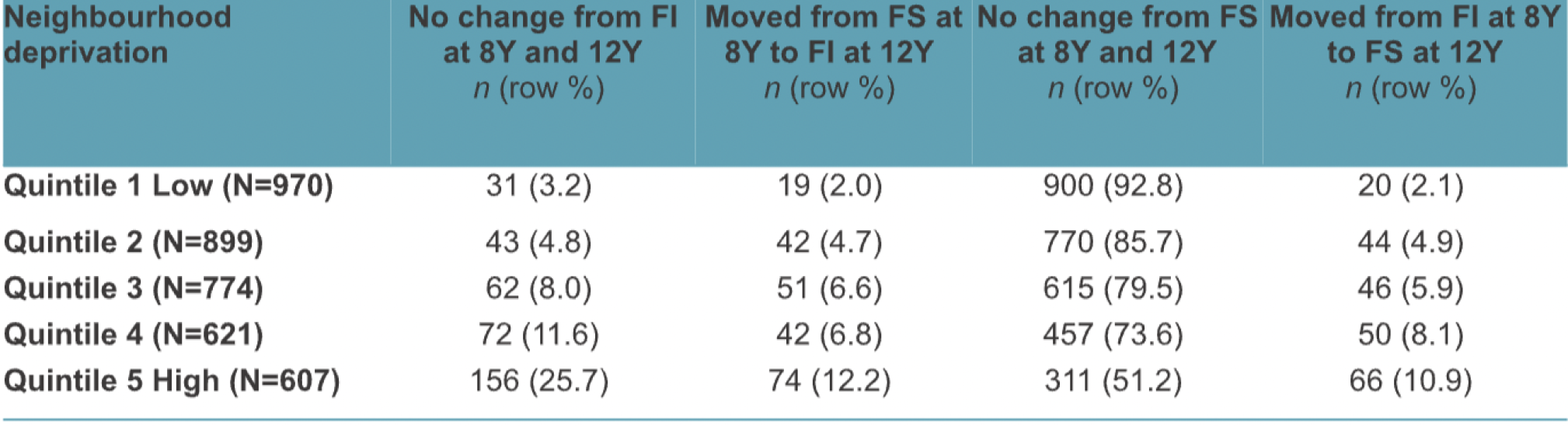

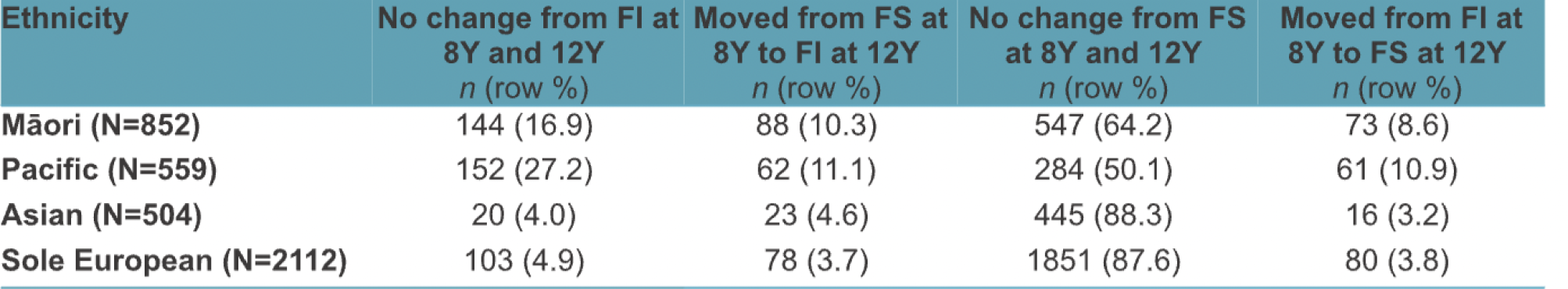

The proportion of young people living in food secure households at 8-years and 12-years of age was similar (84.5% and 83.1% respectively). However, rangatahi Māori, Pacific young people, and those in the most deprived neighbourhoods were most likely to be persistently food insecure, or to move from food security to food insecurity, in those four years.

Note: * Missing means that the mother did not answer the questionnaire at that time point.

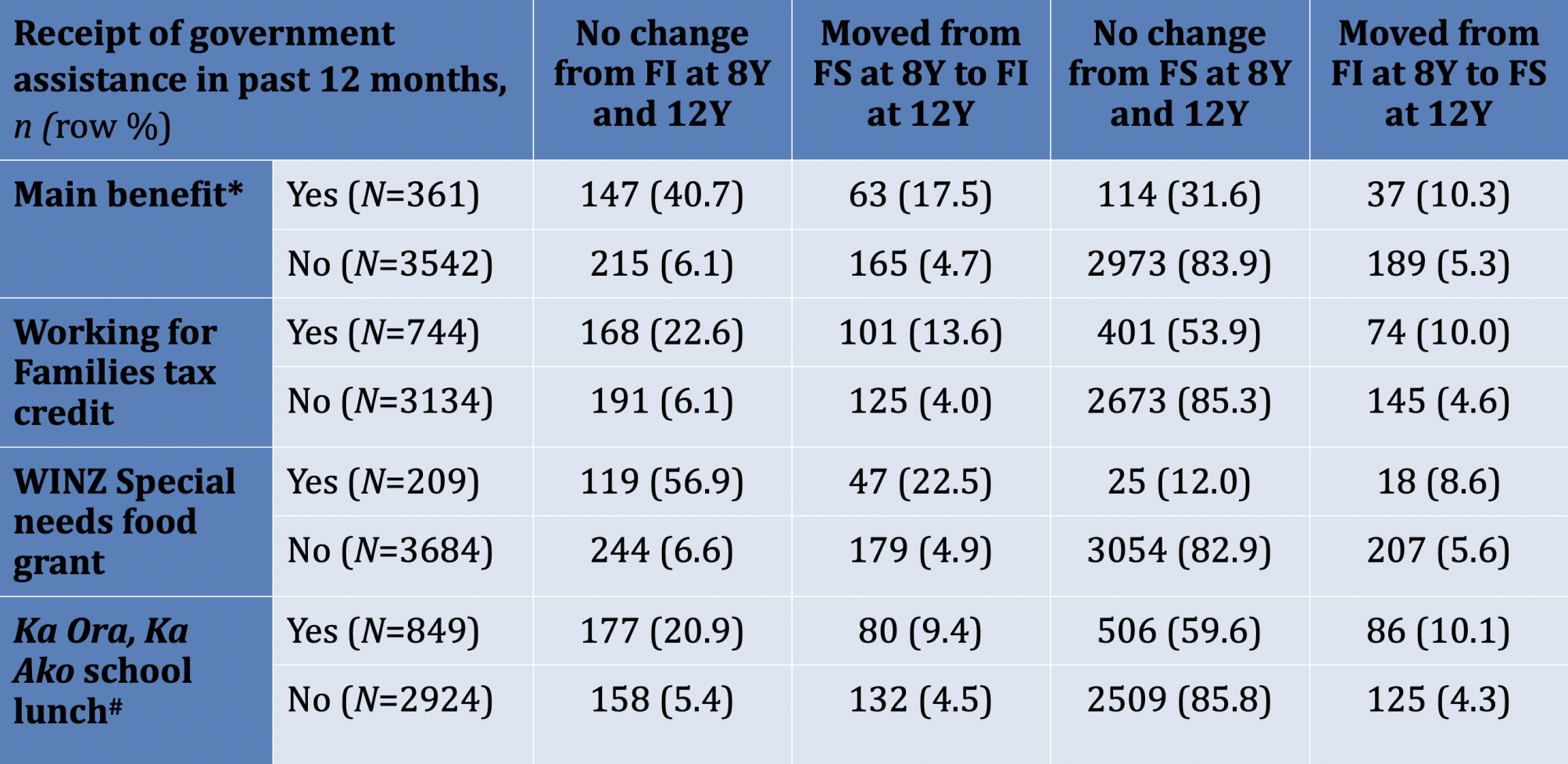

Note: FS= food secure, FI= food insecure (moderately and severely combined). This table only includes data from families that participated at both the 8Y and 12Y DCW (excludes those with missing data) for clarity.

Note: FS= food secure, FI= food insecure (moderately and severely combined). This table only includes data from families that participated at both the 8Y and 12Y DCW (excludes those with missing data) for clarity. MELAA and Other groups not shown due to small numbers.

Insight three

Use of special food grants or food banks increased for households in the past four years.

All indicators of food insecurity decreased among the Growing Up in New Zealand families when their child was 8 to 12-years of age, except for an increase in the proportion using special food grants or food banks.

The prevalence of food insecurity indicators in the Growing Up cohort is the same (within the 95% confidence interval margin) as those for 10–14-year-olds in the New Zealand Health Survey, confirming Growing Up in New Zealand’s generalisability to the national population.

The most common indicator of food insecurity experienced by young people at both 8 and 12-years of age was a limited variety of food in the house because of a lack of money.

Mothers also commonly reported feeling stressed about not having enough food and feeling stressed because they could not provide food for special occasions.

The next most common indicators of food insecurity were the family eating less and food running out in the household because of a lack of money.

Less commonly, mothers reported using special food grants or food banks and having to rely on others to provide food or money for food.

The relative order of prevalence for these indicators was the same for each of the main ethnicities.

Footnotes: N=4045 at 8Y and N=4310 at 12Y.

Insight four

Government financial assistance helps to alleviate food insecurity for some families but is generally not enough.

Young people that lived in households receiving main benefits or Working For Families (WFF) tax credits were more likely to be persistently food insecure, or to move into food insecurity, from the ages of 8 to 12-years compared to other young people; with over half of main benefit recipients characterised as food insecure at both time points.

- We weren’t eligible (n=55)

- Covid-19/Lockdown (n=23)

- The amount was not enough [or similar] (n=15).

Notes: * Main benefit = Jobseeker Support, Sole Parent Support or Supported Living Payments in the past 12 months, # Yes = Irregular users of Ka Ora Ka Ako (n=100) have been combined with those receiving Ka Ora Ka Ako most or every school day (n=749).

Insight five

Most school food programmes are only available in low advantage (low decile/ Equity Index) schools, but many 12-year olds experiencing food insecurity did not attend low advantage schools.

One in four 12-year olds were receiving food at school most or every school day, with 20% receiving Ka Ora, Ka Ako, the Government’s healthy school lunch programme. Half of the young people living in moderately food insecure households, and a third of those living in severely food insecure households, did not receive Ka Ora, Ka Ako in the past year.

Relevance for policy

and practice.

Targeting of food security policy misses a large number of those affected.

Food insecurity continues to be a pressing issue for about one in five young people growing up in New Zealand. Additionally, our longitudinal research has established that it is not always the same one in five young people affected at different time points. Cumulatively, there are many more children exposed to food insecurity at some stage during their development than at one age or timepoint. In other words, household food security status changes and is a precarious situation. This, together with the fact that children across the spectrum of diverse neighbourhoods and characteristics may experience food insecurity, confirms other recent research showing that the targeting of policy responses to certain groups, schools or areas is counterproductive as it misses a large number of those affected.

Government financial assistance helps families in need but is not currently enough.

Our research also supports the Welfare Expert Advisory Group’s finding that household incomes are inadequate to provide a basic standard of living for many children (with over half of households receiving main benefits classified as food insecure), but shows government assistance can make a difference. Households experiencing food insecurity and receiving a main benefit or Working for Families tax credits were twice as likely to move to being food secure four years later, compared to those in the same position that did not receive government financial assistance. The recent (April 2022) increases to main benefits and Working for Families tax credits will have further improved the finances of eligible families but they may not be sufficient, given that over half of households receiving main benefits were food insecure. Additionally, to ensure support for other families facing food insecurity, abatement thresholds and eligibility for tax credits and food grants should be reassessed.

The number of schools in the Government’s healthy school lunch programme should increase.

The consistently high number of young people living in food insecure households provides a clear policy justification for Ka Ora, Ka Ako, the Government’s healthy school lunch programme. However, the targeting of Ka Ora, Ka Ako to ~25% of schools using the Equity Index has meant that up to half of young people living in food insecure households do not have access to this food assistance programme. To improve Ka Ora, Ka Ako's reach, policy makers should consider increasing the number of schools in the programme, as also recommended by Health Coalition Aotearoa. The value of Ka Ora, Ka Ako extends beyond its primary aim of feeding hungry children, with the potential to improve the nutritional status and eating behaviours of the whole child population, particularly given the revised nutrition standards for the programme implemented from 2023.

References and

research methods

At Growing Up in New Zealand, we're passionate about advancing research and making sure our work is informed by a wide range of sources. That's why we've included a comprehensive list of references, along with an introduction and a detailed report of the research methods used to support the Growing Up in New Zealand study.

Read the full report

We’ve carried out more than 90,000 interviews and collected more than 50 million pieces of data to help inform policy and help give children the best start in life.

Explore other snapshots

%201.svg)