School engagement

The New Zealand Government is committed to supporting all young people to reach their learning potential (1). Understanding how young people engage in school and identifying who is at risk of lowered school engagement is vital for establishing pathways that support ākonga (student/s) and ensuring equity in educational outcomes. Engaged learners are, on average, more regularly involved in school and learning activities, have a deeper sense of school connectedness, and have better achievement outcomes (2-4). This report examines the factors associated with school engagement and highlights four priority recommendations for policy and practice based on these findings.

- Continue to foster and promote inclusive school environments.

- Promote the importance of student-teacher relationships and build student’s academic efficacy.

- Promote whole-school approaches that enhance inclusive and responsive environments.

- Improve access to services and support for mental wellbeing.

This report provides an overview of young people's engagement in school and identifies key factors associated with engagement.

What is School Engagement?

Consistent with recent research (5), we considered school engagement to include elements of behavioural engagement (actions ākonga are taking in their learning), emotional engagement (their feelings towards learning and school), and cognitive engagement (thinking deeply about their learning).

School Engagement Measure: In total, 17 items were used to measure school engagement, including the behavioural (6), cognitive (7), and emotional (8) components of school engagement. Young people’s responses to these 17 items were used to derive an overall school engagement score. See supplementary material for more information on how this was derived.

We investigated school engagement in three ways:

- How does school engagement relate to gender and ethnic identity, deprivation, and learning needs?

- How has emotional school engagement changed over time? We considered emotional engagement at age 8 (before the Covid-19 pandemic), at the start of the pandemic (at approximately age 10) and again at age 12.

- A multiple regression analysis was conducted to consider the factors associated with school engagement at age 12.

School engagement scores ranged from 1–5, with higher scores representing reports of higher levels of engagement and lower scores representing lower feelings of engagement. For more information, see the supplementary material.

Insight one

In general, most young people reported positive school engagement.

Our study found that most young people were positively engaged at school with a mean score of 3.76 (standard deviation = 0.69). However, a sizeable proportion (14.3%) of young people scored below three, indicating these learners had less positive school engagement experiences.

Overall, the mean school engagement score at age 12 was 3.76.

14.3% of young people had less positive school engagement experiences.

Note: This figure shows the distribution of school engagement scores at age 12. A score of 1 indicates very low school engagement; whereas a score of 5 indicates very high school engagement.

Insight two

Across young people of all ethnicities, transgender/non-binary young people reported the lowest school engagement; whilst cisgender girls reported the highest school engagement.

Our results show that aspects of school engagement are experienced differently based on gender identity and ethnic identity.

On average, Asian young people had the highest scores.

Rangatahi Māori had the lowest school engagement scores, on average.

For cisgender girls the distribution skews towards higher engagement.

Gender diverse young people tended towards lower mean scores.

These trends were consistent across all ethnicities.

Insight three

Young people with certain types of additional learning needs reported lower school engagement than ākonga with no additional learning needs.

When compared with children who had no identified learning need, children who were reported to have the following difficulties/learning needs had, on average, significantly lower school engagement scores:

Specific learning disability (e.g. dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia).

Autism.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Emotional or behavioural problems.

Those requiring extra subject-specific support.

School engagement differed by type of additional learning need.

On average, those with emotional or behavioural problems and/or ADHD had the lowest school engagement scores.

Young people identified as having no additional learning need were those whose parents indicated that they had no additional learning needs at school.

Sensory impairment includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to a hearing or vision impairment.

Speech and/or language impairment includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to a speech and/or language impairment.

Learning disability/intellectual disability includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to a learning disability/intellectual disability.

Specific learning disability includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to a specific learning disability (literacy, previously known as dyslexia), specific learning disability (numeracy, previously known as dyscalculia), specific learning disability (writing, previously known as dysgraphia), developmental coordination disorder (also known as dyspraxia) and/or auditory processing disorder (APD).

Gifted and talented includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to being gifted and/or talented with an exceptional ability in one or more learning area (e.g., intellectual ability, culture-specific, creativity, visual and performing arts, social/leadership, physical/sport).

Autism includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to autism spectrum disorder.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Emotional or behavioural problems includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to emotional or behavioural problems.

Extra subject specific support includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need as extra subject specific support was needed.

Other includes those young people whose parents reported that they had a learning need due to a physical disability, poor understanding of English and/or was an English speaker of other languages (ESOL), illness or any other learning need not previously described.

Insight four

Emotional school engagement has improved for young people since early in the COVID-19 pandemic (May 2020); however, it is lower at age 12 than at age 8.

Compared to at age 8, emotional engagement scores dropped sizeably at the start of the pandemic when most children were learning from home. Overall, there was some recovery in emotional engagement by age 12, however, this was not to the extent of pre-COVID times. This shift in emotional engagement may be related to the Covid-19 pandemic and changes in school modality (e.g. learning from home); however transitions between schools and/or other age-related factors may also have contributed to this shift.

At age 8, the average emotional engagement score was 4.01 (SD = 0.83), with a broad distribution of emotional engagement which tended towards higher emotional engagement scores.

At age 10, early in the pandemic, the average school engagement score was 3.11 (SD = 1.01), with a broad distribution of emotional engagement which tended towards lower emotional engagement scores.

At age 12, the average school engagement score was 3.52 (SD = 1.00), with a broad distribution of emotional engagement scores.

Insight five

Student-teacher relationship is strongly associated with student engagement

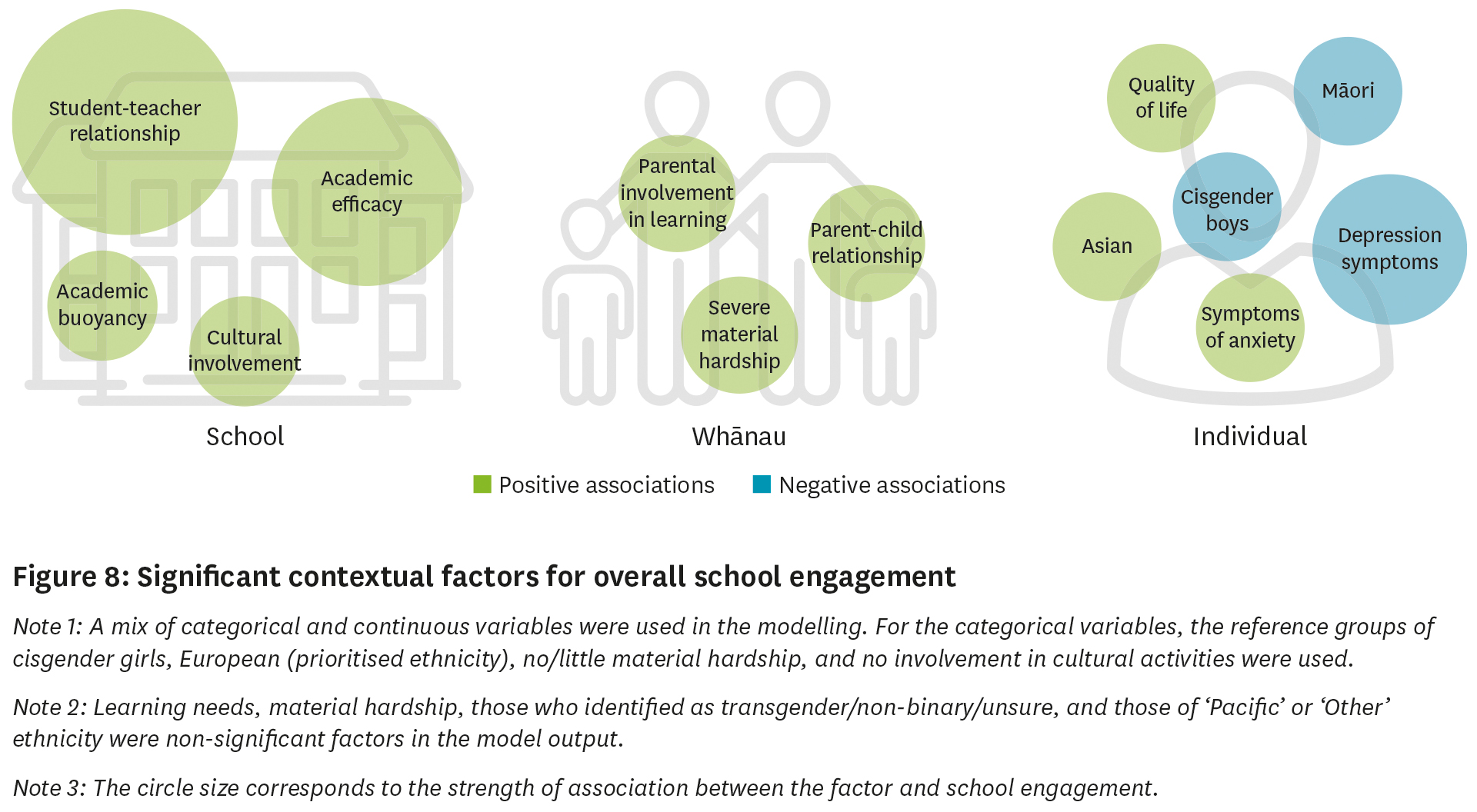

School-related factors, particularly student-teacher relationship and academic efficacy were found to have the strongest positive relationship with school engagement. Family/whānau-related factors had a small but significant positive association, suggesting home life also plays a vital role in schooling. Whilst ethnicity and gender identity were important factors in the model, depression symptoms had the greatest negative association with school engagement.

This figure provides an overview of the results from the multiple linear regression, which was used to examine how school, whānau/family, and personal factors were associated with school engagement. Positive associations are shown in green; negative associations are shown in blue. The strength of the association is represented by the size of the circle.

Note 1. Learning needs, material hardship, those who identified as transgender/non-binary/unsure, and those of ‘Pacific’ or ‘Other’ ethnicity were non-significant factors in the model output.

Note 2. The reference group for ethnicity was European. The reference for gender identity was cisgender girls.

Relevance for policy

and practice.

This report has examined the school engagement of young people in New Zealand

This report's findings suggest that more emphasis is needed on creating inclusive and responsive environments within NZ to ensure that all young people are positively engaged in school. Whilst the findings of the multivariate modelling showed that student-teacher relationships, students’ academic efficacy, and reports of depression symptoms had the strongest associations with school engagement at age 12, it is important not to lose sight of what the univariate analysis revealed concerning inequities. That is, at age 12, rangatahi Māori, those who identify as transgender, non-binary or those who are unsure of their gender, and students with certain types of additional learning needs were more likely to report lower school engagement.

Recommendation 1:

Continue to foster and promote inclusive school environments

This report supports the New Zealand Government’s Attendance and Engagement Strategy (9), which highlights the importance of providing a school environment where ākonga feel safe, see their individual identities and cultures reflected in the school context, and where strong connections between teachers and ākonga are prioritised. Alongside other strategic documents (1, 9-14), the refresh of The New Zealand Curriculum currently underway (15) places a focus on acknowledging the cultures, identities and strengths of ākonga. Inclusive schools would ensure all young people feel supported and have a sense of belonging within their school environment.

Recommendation 2:

Promote the importance of student-teacher relationships and build student’s academic efficacy

Policymakers and schools are encouraged to continue focusing on providing opportunities to enhance the student-teacher relationship in schools and promote academic efficacy. This includes supporting teachers to build the skills needed to form positive relationships with ākonga, so that they feel that they are listened to, respected, treated fairly, and can approach their teacher for help. An emphasis should also be placed on young people developing beliefs that they can be successful in their learning; beliefs which are more likely developed in positive, error-friendly learning environments, where people feel they belong, negative stereotypes are actively critiqued, mistakes are viewed as teachable moments that show we are learning, and where help-seeking is encouraged (16-21).

Recommendation 3:

Promote whole-school approaches that enhance inclusive and responsive environments

The Ministry of Education has several resources that align with this recommendation.

See:

- Guide to LGBTIQA+ Students

- Putting Student Relationships First

- Inclusive Practice

This study suggests that certain individuals may report lower engagement than others. Frameworks such as the Minority Stress hypothesis offer insight into where discrimination and oppression are correlated with mental health concerns, including depression (22). The groups in this study that are more likely to report low engagement may face additional stressors from racism, able-ism, homophobia, and transphobia, compared to students that are not discriminated against in these ways. Schools are a great place to provide intervention for mental health concerns and to critique such stereotypes (for example, the SOAR programme). Efforts to eliminate discrimination and oppression, and the ensuing stress it produces, are critical to improving mental health outcomes for minoritised groups.

.png)

Recommendation 4:

Improve access to services and support for mental wellbeing

Recent government initiatives have been developed to support students mental health (e.g., TKI Resource: Mental Health Education: A guide for teachers , leaders and school boards).

While monitoring and supporting student wellbeing requires support across all areas of young people’s lives, additional support for schools may help them to better equip teachers and school staff to support students’ wellbeing through professional development and training. This may include (but is not limited to) how to talk about and recognise early warning signs of low mood (in self and others), how to discuss mental health with young people, strategies young people can use to help themselves or others, and what services are available.It is also crucial that young people can readily access early intervention services such as counselling when they experience low mood. For example, free youth-friendly counselling services should be easily accessible and widely available within schools and the community.

References and research methods

At Growing Up in New Zealand, we're passionate about advancing research and making sure our work is informed by a wide range of sources. That's why we've included a comprehensive list of references, along with an introduction and a detailed report of the research methods used to support the Growing Up in New Zealand study.

Read the full report

We’ve carried out more than 90,000 interviews and collected more than 50 million pieces of data to help inform policy and help give children the best start in life.

Explore other snapshots

%201.svg)