Structural disadvantage and rangatahi Māori mental wellbeing

Rangatahi Māori experience consistent and compelling inequities across a range of outcomes compared to Pākehā young people, including self-reported health status, health risk behaviours, and forgone healthcare (1). Of particular concern is the increase in the prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms amongst Māori secondary school students over time, from 13.8% in 2012 to 27.9% in 2019. Rangatahi mental health is therefore considered a major public health problem (2-3).

Structural disadvantage affects rangatahi Māori mental wellbeing in various ways including through differential exposure to stressors (e.g. racism, discrimination, poverty) and stressful life events (e.g. moving, death of a family member, contact with police, being a victim of violence). Structural disadvantage also limits rangatahi Māori access to high quality mental health care from assessment and diagnosis through to treatment and recovery (4). The harms caused by structural disadvantage can be both direct (i.e. experienced by rangatahi Māori themselves), or indirect/vicarious (i.e. experienced by others in their group, including whānau) (5-6). Structural disadvantage is therefore an important part of the causal pathway linking colonialism and racism to inequities in Māori health outcomes.

Research shows that cultural connectedness is independently associated with positive mental wellbeing, including in rangatahi Māori (7). However, there has been no investigation of the potential for cultural connectedness to act as a buffer against the harms caused by structural disadvantage on rangatahi Māori mental wellbeing.

- Ngāpuhi, Tainui, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Porou and Ngāi Tahu/Kāi Tahu were the five most frequently reported iwi of the 115 iwi identified by rangatahi Māori in this study.

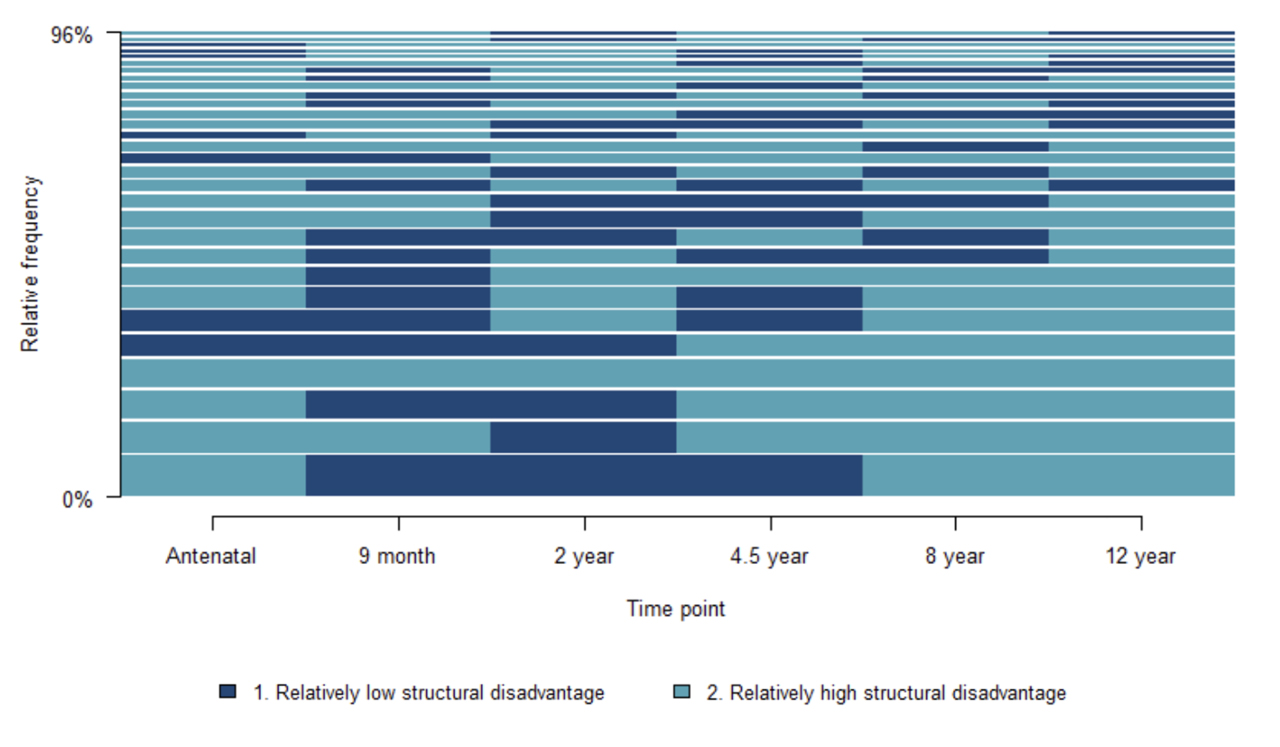

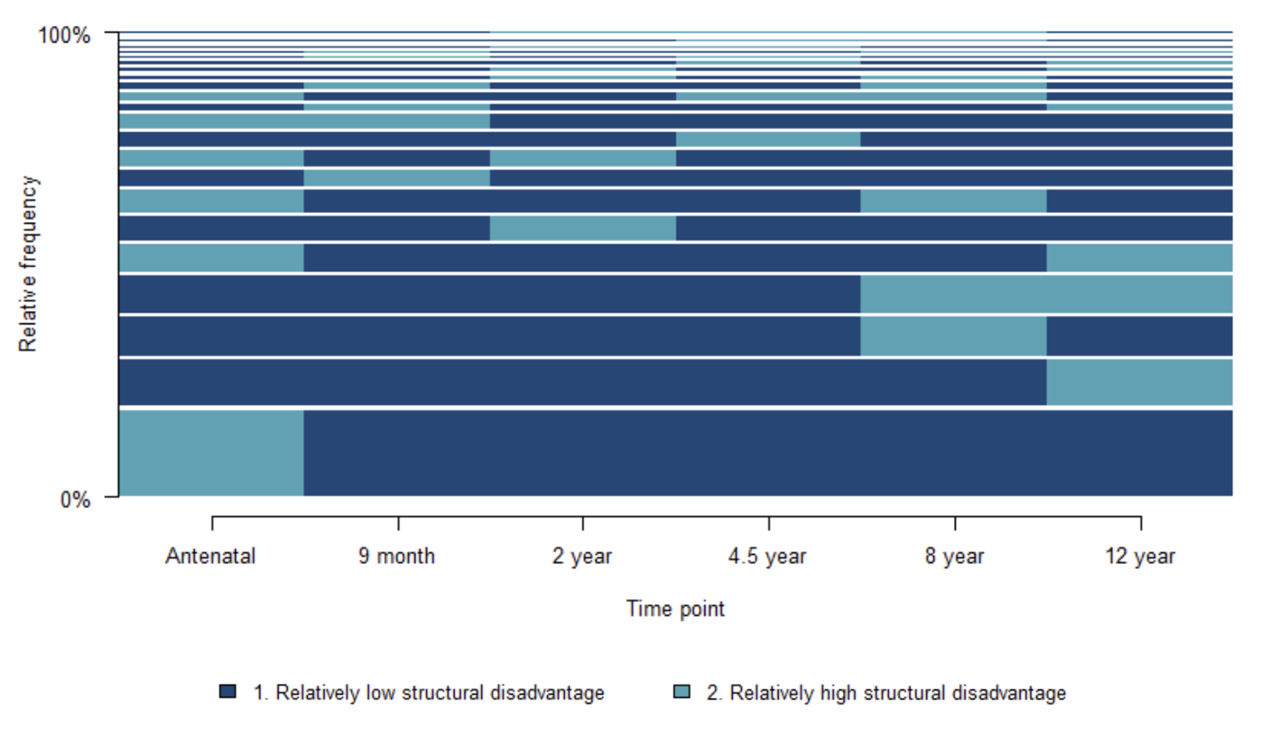

- 21% of rangatahi Māori experienced persistent and relatively high levels of structural disadvantage. Many rangatahi Māori in this group experienced structural disadvantage across most of their lives.

- 35% of rangatahi Māori experienced intermittent periods of relatively high structural disadvantage;

- 44% of the rangatahi Māori cohort experienced persistent and relatively low structural disadvantage;

This paper provides the first contemporary information about trajectories of structural disadvantage for rangatahi Māori, using data collected from before the Growing Up in New Zealand cohort were born through to 12-years of age.

Structural disadvantage refers to the disadvantage that some individuals and/or groups experience due to the unfair distribution of power and resources that exist within society. In Aotearoa New Zealand, colonisation and racism are the systems that actively organise and allocate advantage and disadvantage according to social status categories, such as ethnicity, gender and age (8-9). Intergenerational transmission helps us to understand how processes of colonisation, such as land loss, political marginalisation, cultural subjugation and socioeconomic deprivation (9-10), shape Māori experiences of structural disadvantage including through inequities in access to the social determinants of health such as income, education, housing and employment that persist across generations.

The comprehensive measurement of mental wellbeing in the study enables us to investigate whether trajectories of structural disadvantage are associated with different mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety symptoms as well as quality of life (a more global measure of wellbeing). This provides more nuance and detail about the experiences of structural disadvantage from lifecourse perspective, which is important for development of policies that better meet the needs and priorities of rangatahi Māori. Finally, the paper makes an important contribution by exploring whether cultural connectedness buffers the harms caused by structural disadvantage on rangatahi mental wellbeing.

Mental wellbeing was examined at 12-years of age using three different indicators including depression symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 10-item Short Form, (11)), anxiety symptoms (8-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS, (12)) Paediatric Anxiety - Short Form 8a questionnaire) and quality of life (10-item KIDSCREEN questionnaire, (13)). Structural disadvantage was measured using a range of indicators reported by the mothers of rangatahi Māori at the antenatal, 9-month, 4.5-year, 8-year and 12-year data collection waves (DCWs), including household material hardship (Dep-17 Index, (14)), neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation (NZ Deprivation Index (15)), maternal employment status (employed vs unemployed), and residential mobility (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4+ moves since the last DCW). Home ownership status was used as a proxy for residential mobility at the antenatal DCW. It is important to remember that we are comparing experiences within the rangatahi Māori cohort, therefore the use of “relative structural disadvantage” refers to rangatahi Māori experiences of structural disadvantage relative to other rangatahi Māori in the Growing Up in New Zealand study, and not to non-Māori in the Growing Up in New Zealand study or in Aotearoa more generally. This approach assumes that all rangatahi Māori experience structural disadvantage, and we are interested in how this experience plays out across childhood. Cultural connectedness was measured at the 12Y DCW using the sum score of the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) instrument, which includes 12 statements to determine sense of belonging and strength of connection to one’s ethnic group(s) (16). Details about each of the measures and other covariates can be found in the Supplementary Materials for this paper.

Insight one

More than half of rangatahi Māori experienced at least one period of structural disadvantage from prebirth to early adolescence.

Information about structural disadvantage was collected six times from pregnancy through to early adolescence. As well as describing rangatahi Māori experiences of structural disadvantage at 12-years of age, we have identified three trajectories of relative structural disadvantage: persistent relative high structural disadvantage, intermittent relative high structural disadvantage and persistent relative low structural disadvantage.

1 in 5 rangatahi Māori experienced persistent relative high structural disadvantage across most of their lives.

35% of rangatahi Māori experienced intermittent relative high structural disadvantage. Rangatahi Māori in this group experienced more time in relative low, than relative high, disadvantage across childhood.

44% of rangatahi Māori experienced persistent relative low structural disadvantage.

Insight two

The relationship between structural disadvantage and rangathi Māori mental wellbeing is complex.

We identified few associations between longitudinal trajectories of relative structural disadvantage and rangatahi mental wellbeing. This does not mean that trajectories of structural disadvantage are not important for rangatahi Māori mental wellbeing. Rather, it means there were only a few instances where depression, anxiety and quality of life scores differed between rangatahi Māori in the persistent or intermittent high structural disadvantage groups compared with those in the persistent low structural disadvantage group, net of other important factors included in our models, including gender identity and racial discrimination.

There was a weak association between persistent relative high structural disadvantage (vs. persistent relative low structural disadvantage) and depression symptoms score (p=0.055).

However, this relationship disappeared after adjustment for a range of important confounders (p=0.908).

To understand what this might mean for rangatahi depression symptoms, we can use the findings to create a range of

scenarios.

Note these scenarios were calculated based on the final regression model which included the variables of racial discrimination and cultural connectedness, as well as the interaction between relative structural disadvantage and cultural connectedness. See Supplementary Materials for more information.

For rangatahi Māori in the persistent relatively low structural disadvantage group who are not experiencing racial discrimination and have high cultural connectedness, their depression symptoms score is predicted to be 8.63. We consider this to be a “best case” scenario.

For rangatahi Māori in the persistent relatively high structural disadvantage group who experience racial discrimination and have low cultural connectedness, their depression symptoms score would be 12.88. We consider this to be a “worst case” scenario.

Insight three

Cultural connectedness is important for mental wellbeing, however it may not support depression and anxiety symptoms and quality of life in exactly the same way.

Higher cultural connectedness was associated with lower depression symptoms (p=0.004) and higher quality of life (p<0.001), but not anxiety symptoms. However, there was mixed evidence that cultural connectedness buffers the relationship between structural disadvantage and depression symptoms for rangatahi Māori.

Using depression symptoms as an example, we found a number of interesting relationships:

Starting with the persistent high disadvantage group (represented by the blue line), we can see that depression scores (y-axis) remain relatively stable even as cultural connectedness increases (x-axis).

In contrast, amongst the intermittent high disadvantage group (green line), it appears as though depression scores decrease (i.e. lower depression symptoms) as cultural connectedness scores increase (i.e. stronger cultural connectedness).

A similar relationship between cultural connectedness and depression scores is apparent for the persistent low disadvantage group (yellow line). The slope of the line suggests that the effect is somewhere in between that observed for the other two trajectory groups.

However, none of these relationships were significant, indicating that cultural connectedness did not have a buffering effect on depression symptoms. There was also no significant buffering effect of cultural connectedness on quality of life scores for rangatahi Māori.

Different patterns were observed when we looked at anxiety symptoms:

There was some evidence of a small but significant buffering effect of cultural connectedness on anxiety symptoms for the intermittent high structural disadvantage group (p=0.05). That is, anxiety scores decrease as cultural connectedness increases.

In contrast, for the persistently low and persistently high structural disadvantage groups, we can see that anxiety symptoms increase as cultural connectedness increases.

Relevance for policy

and practice.

Structural disadvantage is a pervasive and omnipresent threat to the mental wellbeing of rangatahi Māori.

Structural advantage and disadvantage are like two sides of a coin. Although this paper has not explicitly examined whether inequities in mental wellbeing are associated with trajectories of structural disadvantage for rangatahi Māori compared with European young people, the findings should be understood with the knowledge that when research suggests that one group has less, the implication is that another group has more.

These findings empower government, policymakers, researchers and advocates to take bold and courageous action to address structural disadvantage as a multi-factorial and dynamic experience that has its roots in the colonial and racist systems and structures that exist in Aotearoa today.

Policies that prioritise investment in the early years, including recent initiatives to lift welfare support for families and reduce barriers to early childhood education are important for positive long-term social, health and wellbeing outcomes. However, this paper highlights the need for intergenerational and whānau-centred policies that will support rangatahi Māori and their whānau from pregnancy, through childhood and early adolescence and beyond. Whānau-centred approaches are described as “culturally grounded, holistic, outcome-focused and aimed at enabling self-determination” (17, p.9). While this analysis has focused on rangatahi Māori, our measures of structural disadvantage likely affect all whānau members. This highlights the need for a holistic approach that recognises collective context while also addressing individual needs.

All rangatahi Māori should be supported to achieve positive mental wellbeing.

Kia Manawanui Aotearoa provides the strategic direction for the governments whole-of-system approach to mental wellbeing, including designing out inequity through interventions “that will redress social disparities and disadvantage, including outside of the health system (e.g., employment and housing supports)” (18, p.41). This paper supports the need for such a critical shift in order to transform mental wellbeing outcomes. However, our findings take this further by arguing that achieving oranga hinengaro will require support for all rangatahi Māori regardless of their level of structural disadvantage or access to material resources.

All rangatahi Māori should be enabled to develop a strong sense of identity and feelings of belonging.

Rangatahi Māori have the right to self-determination and to our culture and identity (19). Upholding this right will require policies that enable rangatahi Māori to know our national and local histories, to have opportunities to build their understanding of tikanga Māori and te reo Māori and to be supported to develop a strong sense of identity and belonging in ways that make sense for them. Rangatahi Māori are the experts of their lives and including their voices at the decision-making table is critical for transforming mental wellbeing outcomes (20). This paper reminds us of the tremendous opportunity that exists for government, policy-makers and advocates to partner with rangatahi Māori so that initiatives and programmes reflect their diverse, intersectional and contemporary realities and aligned with the aspirations of te ao Māori.

Cultural connectedness is important for rangatahi Māori mental wellbeing, but it is not a substitute for anti-racism action.

Although this paper has not explicitly examined whether inequities in mental wellbeing are associated with trajectories of structural disadvantage for rangatahi Māori compared with European young people, the findings are broadly aligned with other recent reports which show that rangatahi Māori are more likely to experience material hardship, severe housing deprivation/homelessness, and food insecurity. Achieving the government’s vision of pae ora – healthy futures and mental wellbeing for all – requires actions that will enable rangatahi Māori to develop a strong cultural connectedness not as a resilience or coping strategy but rather as part of a broader Treaty-compliant, pro-equity, anti-racist and human rights-based approach. Anti-racism action will require a commitment to invest in strategies that will systematically dismantle the structures that contribute to inequities in rangatahi Māori mental wellbeing (1,21). This paper provides new insights into the powerful potential of policies that address structural disadvantage and enable rangatahi Māori to flourish in their identity as Māori.

References and

research methods

At Growing Up in New Zealand, we're passionate about advancing research and making sure our work is informed by a wide range of sources. That's why we've included a comprehensive list of references, along with an introduction and a detailed report of the research methods used to support the Growing Up in New Zealand study.

Read the full report

We’ve carried out more than 90,000 interviews and collected more than 50 million pieces of data to help inform policy and help give children the best start in life.

Explore other snapshots

%201.svg)